Rematriating Milk Medicine: Indigenous Breastfeeding Rates on the Rise

For photo captions, hover over the featured image. All images courtesy Indigenous Milk Medicine Week.

Ariel Hansen wishes to acknowledge that she lives on the traditional lands of the Suquamish, Muckleshoot, Duwamish, Stillaguamish and Coast Salish, and to honor the Indigenous people who still live there today.

Wrapped in colorful blankets and herded by US government cavalry, an entire nation walked. The Navajo people walked from the only lands they had ever known, ravaged by the government’s 1864 scorched-earth policy, across more than 300 miles from what is now Arizona to eastern New Mexico. With no assistance from the soldiers, and no information about how long they would be walking or to where, they walked until the most vulnerable died.

Members of the Alamo Navajo Reservation reenact the Long Walk, the forced deportations of the nation from traditional lands in today's Arizona to eastern New Mexico between 1864 and 1866. Comparable to the Trail of Tears, this effort at genocide resulted in collective generational trauma that has persisted in Navajo identity to today.

Photo taken in 2007 by Babbage, used under CC BY 2.0.

“We survived the Long Walk because of human milk, our grandmas being persistent about breastfeeding,” said Amanda Singer, Project Director of the Navajo Breastfeeding Coalition. Had the infants and babies perished, the entire nation might have followed. “It was food that was provided by the holy ones for the future generations.”

Singer and her coalition are among a small group of dedicated advocates working to bring back that reverence for breastfeeding. They hope to boost the low rates among Indigenous nations across North America, the second lowest of any tracked ethnic group. As many as 97 percent of Indigenous parents use formula at least once, despite a large and growing body of evidence for the benefits of human milk.

Rates among Indigenous communities are low for both initiation (whether nursing is begun after birth) and duration (whether or how much a baby is nursed at 6 months old and at 12 months old), according to a 2015 literature review study funded by the US Maternal and Child Health Bureau. However, in the past decade or so, breastfeeding rates have begun rising. Among the Navajo Nation in Arizona, descendants of those on the Long Walk, the percentage of babies fed with nothing but human milk for their first six months went from 15.8 in 2010 to 21.8 in 2020.

While this rise mirrors a trend nationwide, Indigenous advocates call out a unique cause for the rejection of traditional breastfeeding practices: ongoing fallout from colonialism and genocide.

Families continue to contend with a history of confinement on reservations, prohibitions on language and faith practices, broken treaties, and massacres. Children were separated from their parents by religious and social workers who believed they must “kill the Indian to save the man,” as US Army Capt. Richard Pratt repeated in justifying forced cultural assimilation. In residential schools, many children experienced horrific physical and emotional damage, severing them from their cultures. Distant or cruel nuns, priests, and staff members became their only “parents,” Singer said.

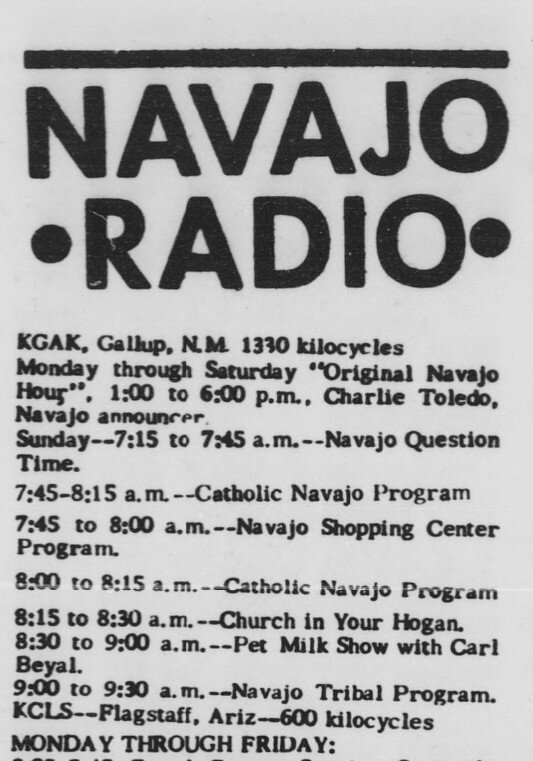

A clip from a 1962 issue of Navajo Times shows a radio schedule featuring a show sponsored by PET Milk. This product, a condensed cow milk, was promoted by respected Navajo leader Annie Wauneka, who advocated for Indigenous public health.

Image clipped from The Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

“When they finally came home, they brought what they learned there,” she said. Some had been sexually assaulted, and when they bore children, their suckling infants viscerally reminded them of that trauma. “They didn’t know how to be a dad, a mom, they lost how to really love a person. A lot of that trickled down the generations.”

At the same time, the Navajo were forced to live close together in increasingly Westernized settings on unfamiliar land. That gave rise to waterborne bacteria that caused severe gastrointestinal disease, claiming babies, children, and elders. Modern sanitation practices hadn’t been necessary before; now, learning how diseases spread was vital, and a respected leader stepped up.

Annie Wauneka, 1910–1997, is widely regarded as one of the most recognized and honored Indigenous leaders of the 20th century. She served 28 years on the Navajo National Council, advocating for Indigenous people, particularly around health issues. She is the only woman to have been honored by her people as “Our Legendary Mother of the Navajo Nation,” and in 1963 she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Lyndon B. Johnson.

Wauneka gave the Navajo the best information she had, explaining the concepts of germ theory, tuberculosis, X-rays, pharmaceuticals, and hospitals, and promoting sanitation and vaccination on reservations. As part of her messaging, she had a weekly radio program. It was sponsored by PET Milk, the company that first canned condensed milk, and Wauneka saw their product as a healthier alternative to unsanitary water.

“My mom remembers hearing her on the radio, listening to her advertising PET Milk, telling people that’s what they should feed their babies,” Singer said.

Jasha Lyons Echo-Hawk, a descendant of the Seminole, Pawnee, Creek, Omaha, and Iowa, is co-founder of Indigenous Milk Medicine Week and a proud “lactivist.” “The marketing was abundant; you were the Joneses if you had formula, if you had a hospital birth,” they said.

August is National Breastfeeding Month

Annually, the four weeks of the month are devoted to a specific focus:

Week 1: World Breastfeeding Week, which highlights the links between breastfeeding and the health of all humans.

Week 2: Indigenous Milk Medicine Week (formerly Native Breastfeeding Week).

Week 3: Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Breastfeeding Week.

Week 4: Black Breastfeeding Week.

To learn more, visit the US Breastfeeding Committee

But the medical system failed to build community confidence, said Singer. At reservation health care facilities, doctors often came and went with the seasons, while trusted long-time providers retired and weren’t replaced. And until recently, most of these doctors were non-Indigenous, and the few who were Navajo absorbed Westernized approaches during their education.

New parents went home from hospitals with free formula, and unsolicited samples arrived in the mail. Companies promised that formula was “just like breast milk,” providing convenience and filling babies up so they slept soundly, said Singer. She worked for the federal government’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, or WIC, before shifting to independent advocacy.

“At WIC I felt like I was competing against formula, because it was being given freely,” she said. “It’s a constant competition against these multimillion-dollar companies.”

In 2008, Singer’s coalition helped pass the “Healthy Start Act” through the Navajo Nation Council. The act requires employers to provide space and time for parents to nurse and pump when they return to work.

“A lot of our grandmas, they would volunteer to talk, to step up and do the Navajo translation for the legislation,” so more Navajo speakers could read it, Singer said. The Westernization of the younger generations has been connected to formula, these elders believe. “They were saying that’s why we’re losing our culture, losing our language, why a lot of our young ones were starting to stray,” said Singer. “They noticed that a lot of health disparities have increased.”

Jaclyn Roessel, a Diné (Navajo) member who lives on the reservation in Santa Ana Pueblo, New Mexico, was breastfed herself and expected to breastfeed. But many of her peers grew up on formula and planned the same for their kids. When her infant son was gaining weight slowly, she felt pressure to turn away from breastfeeding.

“Our main doctor said we needed to start supplementing with formula, and it was something I didn’t want to have to do,” Roessel said. Her mother and mother-in-law supported her determination, and with a lactation consultant’s help, she increased her milk supply and boosted her son’s growth.

Today, Roessel nurses both her son, now two and a half, and her six-month-old—sometimes simultaneously. This tandem nursing garners double takes in her community, despite it having been a traditional practice. “There are a lot of incredulous comments about why am I still breastfeeding the older one.”

With the example set by Roessel, a cultural justice and equity consultant and writer, and other parents who are increasingly choosing breastfeeding, attitudes continue to shift. “I deliberately include my kids in my work because I do work around the importance of Indigenous ways of knowing, decolonizing narratives, so to me it is an active practice of decolonizing,” she said. Reliant on video conferencing during COVID-19, she sometimes nurses on camera when her children are hungry or need comfort. “I don’t apologize for breastfeeding, when I’m on Zoom or even when I was in person.”

Echo-Hawk sees the resurgence of breastfeeding among Indigenous people as part of a healing process, mending cultural fractures caused by genocidal practices in the 19th and 20th centuries. They point to recent research into epigenetics linking human milk and reduced risks of obesity, communicable disease, and cancer—outcomes that transmit down multiple generations.

“It really is about reclaiming a lot, not just dialogue and representation, but talking about the disruption, the ongoing effects in our communities,” Echo-Hawk said. They center mothering in their descriptions of this reversal process, terming it rematriation. “There’s a lot that gets lost on the way, but it’s not impossible to call it back.”

Explore the data

SIDEBAR:

Cultural norms limit data collection

Scientific studies on breastfeeding have been designed using Western cultural norms, including binary gender constructs and assumptions about who is feeding the baby, said Jasha Lyons Echo-Hawk, who is Seminole, Pawnee, Creek, Omaha, and Iowa.

“We’re trying to decolonize the data,” said Echo-Hawk, who has three children, all of whom have been fed their milk. As the co-founder of Native Breastfeeding Week, just renamed Indigenous Milk Medicine Week, they hope to eventually shift from awareness advocacy to expanding data collection to honor the many ways human milk nurtures children.

One of these ways, rarely considered by Western data gatherers, is milk sharing—feeding one person’s milk to another person’s child. Across the US, there are donation networks both formal (involving lab testing and pasteurization) and informal (parents with extra offering it directly to parents without enough). Usually, this involves pumping and freezing, but before those technologies were available, mothers would sometimes simply hand their baby to a lactating relative or community member to nurse.

Many Indigenous activists and lactation representatives describe feeding a baby milk directly from the body as chestfeeding, body feeding, or human milk feeding. The term breastfeeding excludes parents who do not identify as women or have other reasons to be uncomfortable with the term. Echo-Hawk prefers the term milk medicine, as it emphasizes the sacred food the baby is receiving rather than how and from whom.

Editor’s note: For the purposes of this story, “breastfeeding” is used, as it is a common search term. Western names are used for states and nations for the same reason, while acknowledging that these terms are rejected by many Indigenous people.