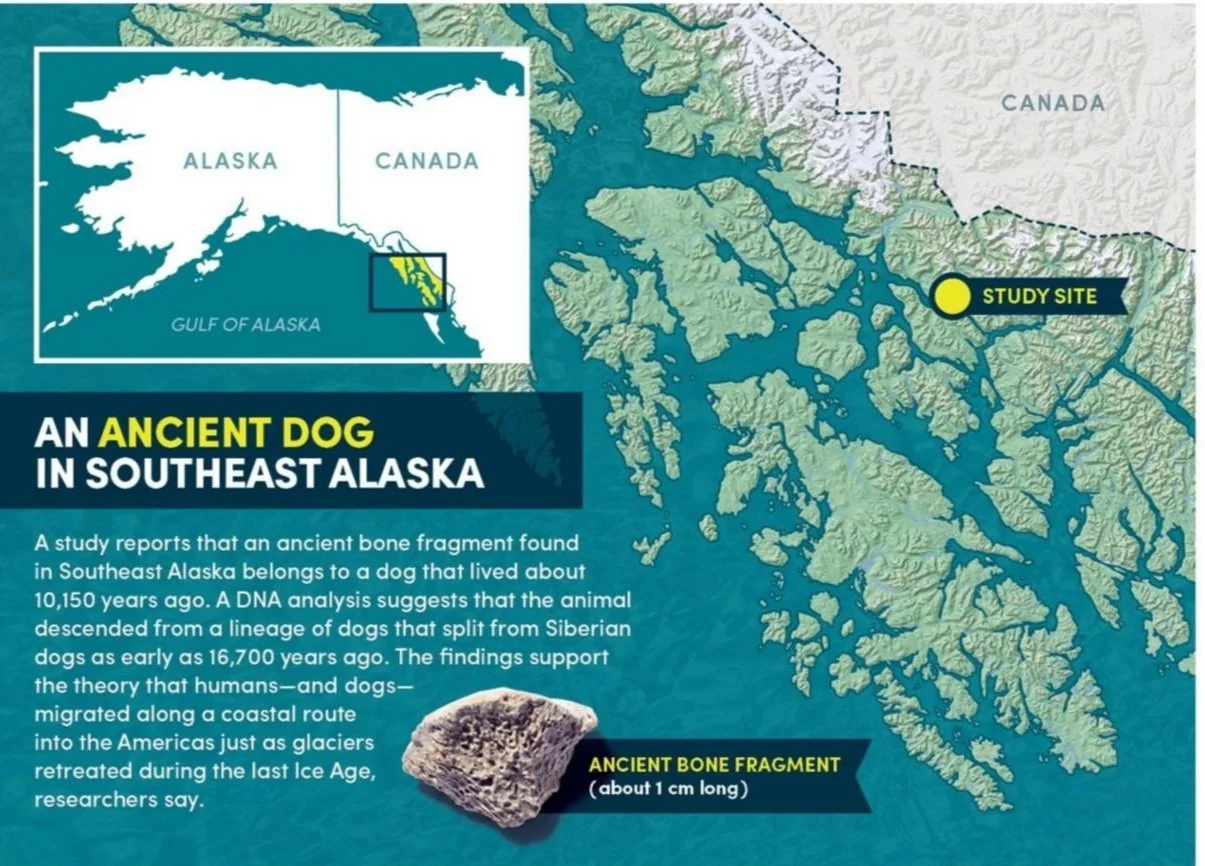

Ancient Dog Bone Sheds Light on Ice-Age Migration

A bone discovered in Alaska suggests domestic dogs may have accompanied humans to the Americas

Image credit: Rawpixel

by Emma Knudsen

January 18, 2022

Tucked away in storage since the 1990s, a porous bone sat in a backlog of remains waiting to be processed by researchers at the University at Buffalo in New York. At only one centimeter long, the fragment was brittle and light. The bone, marked “uncertain mammal,” came from a cave in the southeastern region of Alaska nestled right under Canada.

Researchers began chipping away at identifying this collection of unknown bones earlier this year in a quest to understand southeast Alaska’s fauna, as well as both human and animal migration patterns into the Americas during the last ice age. What they ended up finding suggests that humans and dogs traveled side by side to the Americas over 10,000 years ago, possibly better friends than we previously knew.

Flavio Augusto da Silva Coelho is a doctoral student at the University at Buffalo and a lead author of a study detailing the findings published in the Proceedings of The Royal Society B earlier this year. Coelho and his team delicately brought the fragile bone to the lab for examination, fully expecting to see the typical mitochondrial DNA sequence of a bear, as they had encountered many times before. Ancient bear remains are found with some frequency in this region of Alaska, and their bone fragments are large enough to study. In fact, most of the team’s research focused on ancient bears.

This bone fragment, found in southeast Alaska, belongs to a dog that lived about 10,150 years ago. Scientists say the remains, a piece of a femur, provide insight into the question of when dogs and humans first entered the Americas, and what route they took to get there. Image credit: Douglas Levere, University at Buffalo

Instead, the team was stunned to realize they were holding a bone fragment that might help scientists piece together human migration during the last ice age more clearly. The DNA was of a dog. An approximately 10,150-year-old dog, give or take a couple of hundred years.

“The first thing we thought was, ‘well, it’s contamination,’” remarked Coelho. Perhaps a speck of DNA polluted its purity. Ancient DNA is subject to years of possible contamination, so it was not out of the realm of possibility. However, once they ran additional tests, the analysis confirmed the bone belonged to a group of precontact dogs—canines that existed in the Americas before European settlers brought their domesticated dogs from overseas. It is thought that precontact dogs might have acted as guards, hunters, transporters, and even bed warmers to humans. Closely related to ancient Siberian dogs, precontact dogs were later largely eradicated before the arrival of the familiar European breeds we recognize today. This discovery and understanding shed significant light on the route, method, and timeline for dogs’ arrival into the Americas before Europeans arrived.

“Since their domestication, dogs have been tagging along with humans all over the world,” said Angela Perri, an anthropologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who was not involved with this study. “In places where human remains are scarce, dogs may act as valuable proxies for tracking human migration.”

Before this study was published, the earliest known precontact dog bone in the Americas was found in Illinois. Although researchers knew the bone was found in the middle of the continent, they couldn’t explain how it got there.

The southeast Alaskan cave where the “new” dog bone was found is located right along the North Pacific coastal migration route, which scientists have theorized could have been a primary corridor into the Americas during the last ice age. Because the dog bone is located so close to the North Pacific coastal route of migration, scientists believe domestic dogs might have traveled with humans on the journey to the Americas.

“I think understanding dogs is the closest you can come to understanding humans, maybe even better than studying humans themselves,” commented Perri. “Dogs and the way humans have interacted with their dogs is the most accurate reflection of human-animal interactions over time.”

Image credit: Bob Wilder, University at Buffalo

Through carbon isotope testing, the research team uncovered something surprising in the diet of the ancient dog as well: marine life. “Dogs don’t really hunt in the sea,” Coehlo explained. “It might have been a domestic dog, and it was eating the rest of a human’s food.” Based on this, the research team believes it’s possible this ancient dog had a closer relationship with humans and was more domesticated than previously assumed.

“The study shows what can be done with small bits of bone that were previously unidentifiable,” Perri noted, adding that advancements in archaeological sciences will continue to help scientists dissect more information from even the tiniest samples.

Historical timelines like these are difficult to piece together. New research could change the entire framework of what current theories hold. However, the identification of this ancient dog bone holds the clue to support what scientists have been hypothesizing for years.

“For the first time, we have a dog from that area to support the route,” said Coehlo. “It’s incredible.”

Emma Knudsen

Emma Knudsen is a Boston-based science writer and graduate student in the Johns Hopkins University Science Writing Program. With a background in marine science, ecology, and evolution, she enjoys covering a wide range of stories about the animals and environment that make up the complex world we live in.