Our Relationship With the Unknown

How legendary creatures transitioned from sea to sky

Image credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

by Rachel Lense

January 18, 2022

Aflash of light. A peal of thunder. The roiling of a wine-dark sea beneath an iron sky. This liminal chaos—this “wild unknown”—is where the gods play. Humanity has told stories of supernatural monsters like sea serpents for eons.

Ancient Babylon had Tiamat, the primordial creator who avenged her husband’s death in the form of a sea dragon. The Leviathan of the Bible cropped up repeatedly as a giant demon of the sea, eventually thwarted by God upon his triumphant return to Earth. And in Nordic sagas, Thor faced off against Jörmungandr, a serpent so large it encircled the Earth.

Similar tales continued in the West throughout the Middle Ages and into the Age of Exploration, where seamen’s yarns told of shivered sails and close encounters with tentacles and teeth. But what about today? Has modern science eclipsed humanity’s need for these fish stories? Or have the stories evolved with the times, migrating from the seas to the stars? Do they still serve some role in our cultural consciousness?

“Legends are stories people tell each other that they more-or-less believe to be true,” says Barry Pearson, folklorist and English professor at the University of Maryland. But these days, he says, those legends must be smart—logical—to be truly believed. “Science is something we use in contemporary times to give reason for the tales.”

Take Nessie, for instance, the famous monster from Loch Ness in the Highlands of Scotland. It was, until recently, thought to be an extant plesiosaur, a giant marine reptile from the Mesozoic era. In science, this type of discovery is not without precedent. The most sensational example of these Lazarus animals is the coelacanth, a fish thought dead since Cretaceous times and rediscovered off the coast of South Africa in 1938. But where scientists have enough verifiable evidence of coelacanths to return them to the taxonomy of the living, no evidence exists for Nessie.

Yet to say legendary monsters like Nessie, Tiamat, Leviathan, or Jörmungandr exist only as fringe pseudoscience seems to miss the mark. Such legends illuminate our attitudes toward not only the unknown but also our concepts of power and the “other.”

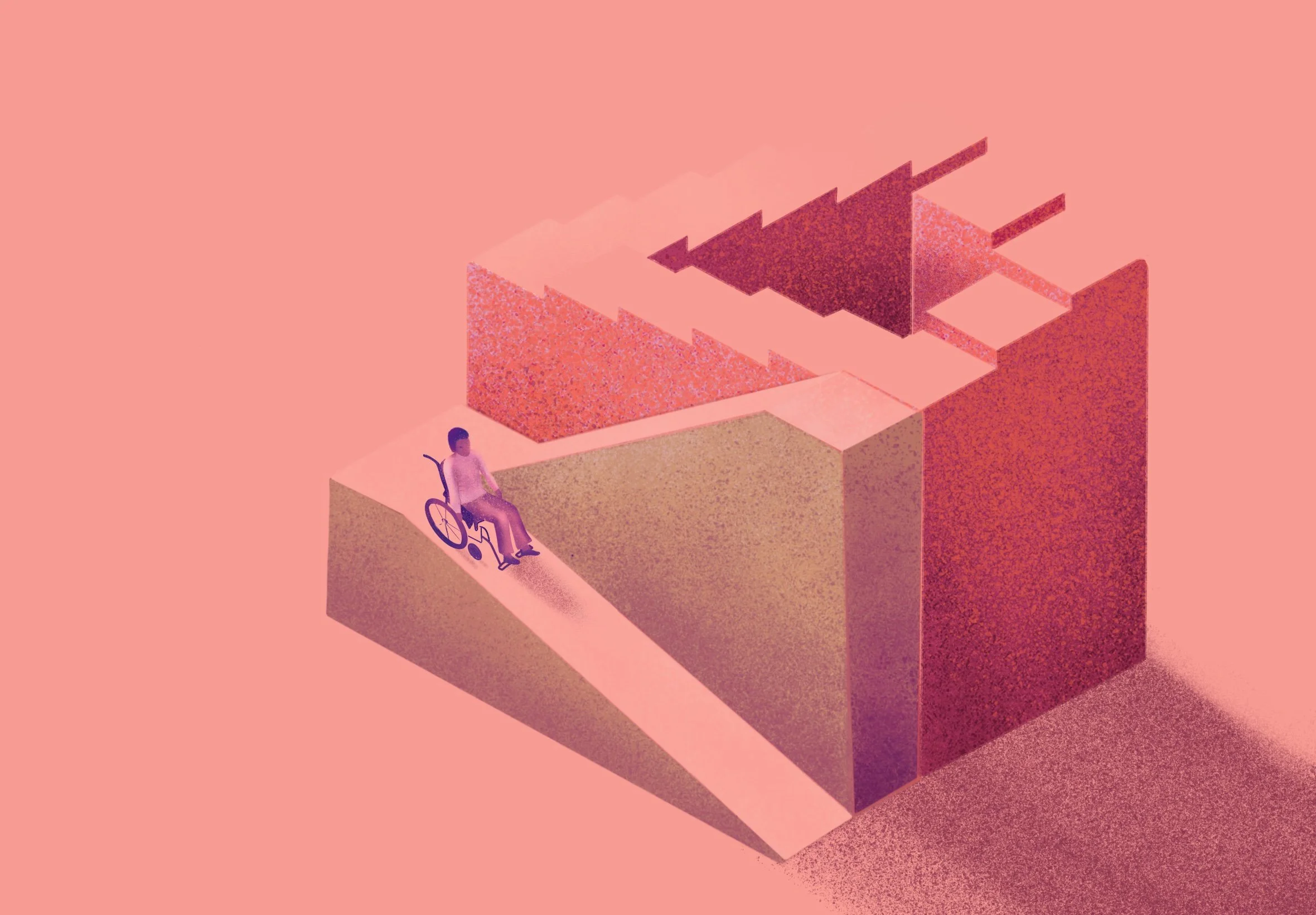

“Mythical creatures mean different things to different people,” says Naveeda Khan, associate professor of anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. Yet they tend to share an exotic power—an otherness. “It isn’t just … that different cultures have different perspectives on supernatural beings, but rather which culture or authority figure is in power.” Medieval Europeans, for example, filled the margins of their maps with all sorts of monsters. “Even though these creatures evoked wonder and … are tied to the emergence of curiosity—which led to exploration, enlightenment, etc.—they’re also tied to certain perceptions of the world outside of the known.” According to Khan, European explorers considered these places “as barbaric, as filled with non-humans or humans who have the characteristics of the non-human and are, therefore, dominatable.” She notes Christopher Columbus’s infamous treatment of indigenous populations in the Caribbean to make her point.

The crux of the mythical beast is that it represents a numinous wilderness, a terra incognita—literally “unknown land.” In the documentary series, Myths and Monsters, Joanne Shortt Butler, a folklorist at the University of Cambridge, defines this unknown territory as “somewhere that is uncultivated, uninhabited by humans. And it's often a liminal space.” Legendary creatures represent a transitional space between the natural and the supernatural—a space on the threshold of understanding.

In prescientific Europe, that space was nearly all-encompassing. In his book On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears, historian and philosopher Stephen T. Asma explains that nature once was seen through a moral or religious lens. However, as time passed and science matured, that lens began to change. In the Western world, Asma states, societies started to believe “that knowledge derives from experimental observation rather than scripture and classical tradition.” He continued: “Science was on the rise, and monsters … were being cleaned up and fit into the new system of uniform natural laws.”

Unicorns became misinterpreted narwhal tusks, and sea serpents became oarfish, frill sharks, and giant squid. In other words, that wilderness of the natural world, that in-between realm of magic and dragons of land and sea, was becoming known. Mundane. But rationalism, it turns out, doesn’t mean the end of magic.

“[N]either science nor superstition ever definitively rules out the other one,” explains Asma. Khan agrees. “Sometimes the rational explanation just doesn’t satisfy the intellect enough.” According to Khan, humans have “a desire for explanation that goes beyond the cause and effect that science can produce.” For many, belief in the supernatural is just more exciting.

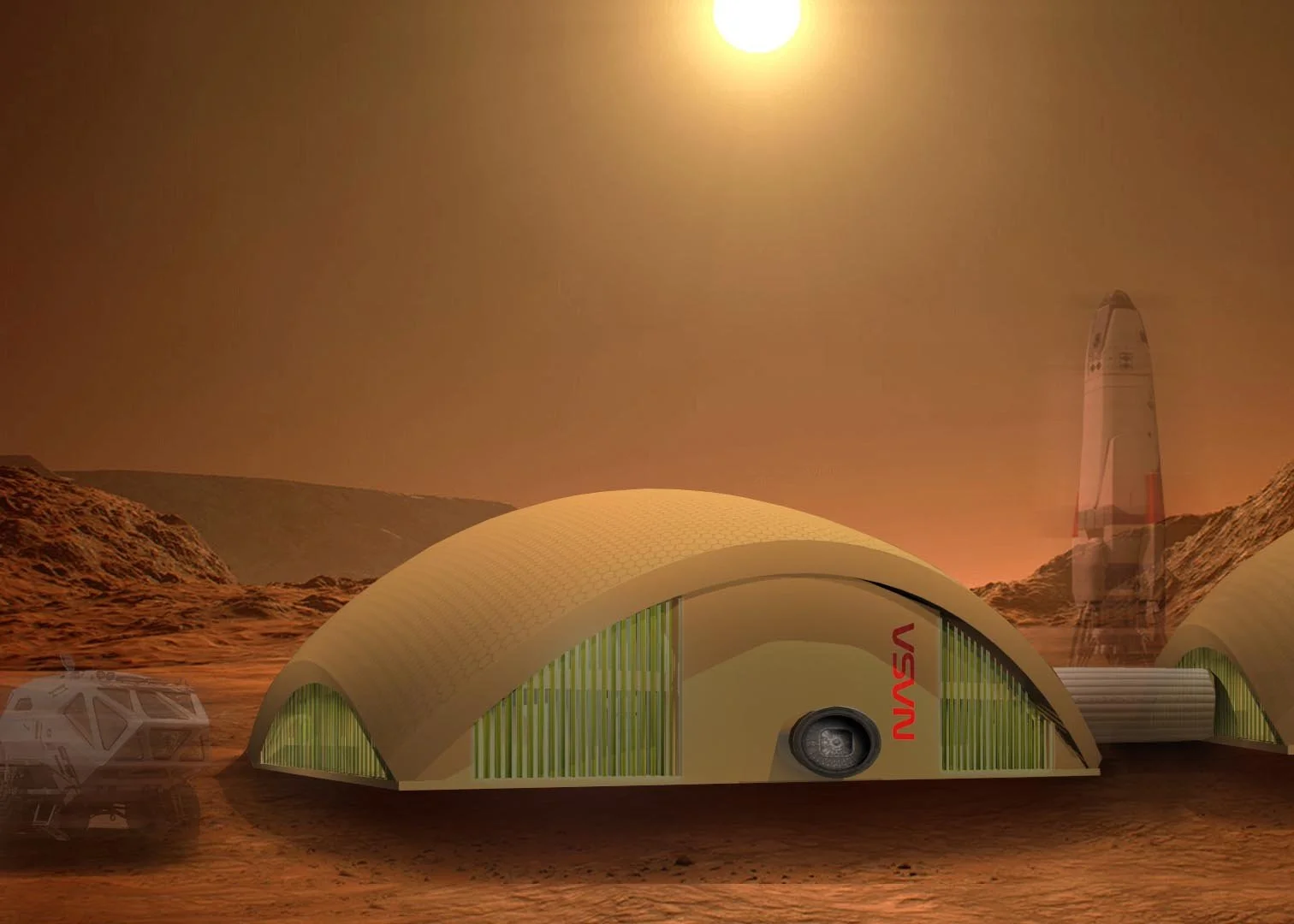

So, where does that leave us in terms of a god-like kraken? Khan thinks they’re done for. “They served a purpose before. You had an empty map, and you had to fill it. And so, you filled it. Now, you don’t need them because the space doesn’t exist. Now they don’t serve any purpose.” But perhaps that map isn’t full if you start looking up. Society accepts that science claims the realms of land and sea, but it also desires the excitement of magic. One area of the natural world may remain largely unexplored and, at least in our modern zeitgeist, populated with powerful, mystical beings: the heavens.

Image credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Many scientists believe alien life exists somewhere in the universe. Famous theories like the Fermi Paradox and the Drake Equation try to divine their existential probabilities outright. And Carl Sagan, a respected cosmologist and science communicator, was influential in establishing the United States’ Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) program. This belief in aliens is mirrored in the opinions of the American public. According to recent Gallup surveys, 75% of Americans believe that “life of some form” exists somewhere in the cosmos, and 41% believe that extraterrestrial life has visited Earth.

In the middle of the 20th century, a rash of UFO sightings occurred. Sputnik, an early Russian satellite, added palpable fear to the lives of everyday people in the United States during the Cold War. Stories of a government cover-up at Area 51 flourished, and, later on, movies like Stephen Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind were box office hits. Amid all this, a book by famed psychologist Carl Jung was published.

In Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, Jung recognized the tumult of the time and posited that new mythology was emerging. “As our time is characterized by fragmentation, confusion, and perplexity,” he wrote, “this fact is also expressed in the psychology of the individual, appearing in spontaneous fantasy images, dreams, and the products of active imagination.”

To Jung, the UFO phenomenon represented a break in our cultural psyche, an unconscious attempt to bring order to a chaotic world. This jives with Khan’s assessment that stories of alien visitation are an expression of anxiety about our human frailty. In folklore, extraterrestrials can travel through time and space, befuddle our senses, rewrite our memories, says Christopher C. French, emeritus professor of psychology at the University of London. They also inhabit one of the most hostile environments humans have yet to discover: a caelum incognita, perhaps. The unknown wilderness of space.

In Myths and Monsters, Diane Purkiss, professor of English literature at Oxford University, provided another definition of wilderness. According to her, the wilderness is “the place where, because you haven't got a big rational take on it, you can fill it with the irrational.” Monstrous irrationalities tie directly to the cultural norms of the people expressing them. For a sea-faring folk like the Norse, a kraken made perfect sense. For those in the United States—a largely secular society, where the supernatural is often explained in scientific or pseudoscientific terms—that cultural norm is aliens. When alien enthusiasts near Rachel, Nevada—the self-proclaimed UFO capital of the world—peer up into the night sky and spy something unusual, there’s a good chance they’ll assume it’s alien. This is due to various psychological factors, including cognitive biases and how our minds process information.

According to French, cognitive biases, or irrational ways our brains interpret the world around us, are experienced by everyone. They’ve helped to keep our species alive by allowing us to make probabilistic judgments with incomplete information. Avoiding the consumption of some mushrooms, for instance, is good if you want to avoid being poisoned. But if you overgeneralize and avoid all mushrooms, you’ll miss out on some varietals’ medicinal purposes or, at the very least, some very tasty meals. Overgeneralization is a type of cognitive bias. Confirmation bias, or the tendency to weigh evidence that confirms your beliefs more heavily than evidence that doesn’t, is another one.

According to French, confirmation bias is one of the strongest and most pervasive cognitive biases. “We don’t need the evidence to be that strong to convince us of something we want to be true, anyway,” he says. Those UFO enthusiasts in the middle of Nevada? They want to see a flying saucer in the desert sky. Seeing a UFO further ingrains their belief that aliens have visited Earth. And because they want to see a flying saucer, in some sense, they do. “Once you’ve got the idea that it might be some kind of alien craft,” says French, “then you get the influence of what psychologists call top-down processing—the way our beliefs and expectations can influence what we see—particularly under poor observational conditions.” Such conditions include the inky darkness of a desert night or the frothing torrent of a stormy sea, where we rely less on cool rationality and more on intuition to interpret the unknown before us. “The notion that [aliens] represent, in many ways, the unknown,” says French, “that’s a plausible idea to me.”

Whether the alien mythos is a direct descendant of Leviathan or some other folkloric archetype, one thing, at least, is certain: it’s a monstrous fish story that’s here to stay—at least until we discover the next proverbial wilderness.

Rachel Lense

Rachel Lense is a writer and photographer who gravitates toward the more fantastic areas of life (philosophizing about robots, writing sonnets about sea creatures, and getting moonstruck over space exploration). She has photographs, poetry, and nonfiction published in print in Red Weather Magazine and online at The Creative Cafe and Get Inside. Some of her favorite things in life include adventuring in far-off lands, savoring delicious foods, and frolicking with her dogs, Zelda and Jasmine.